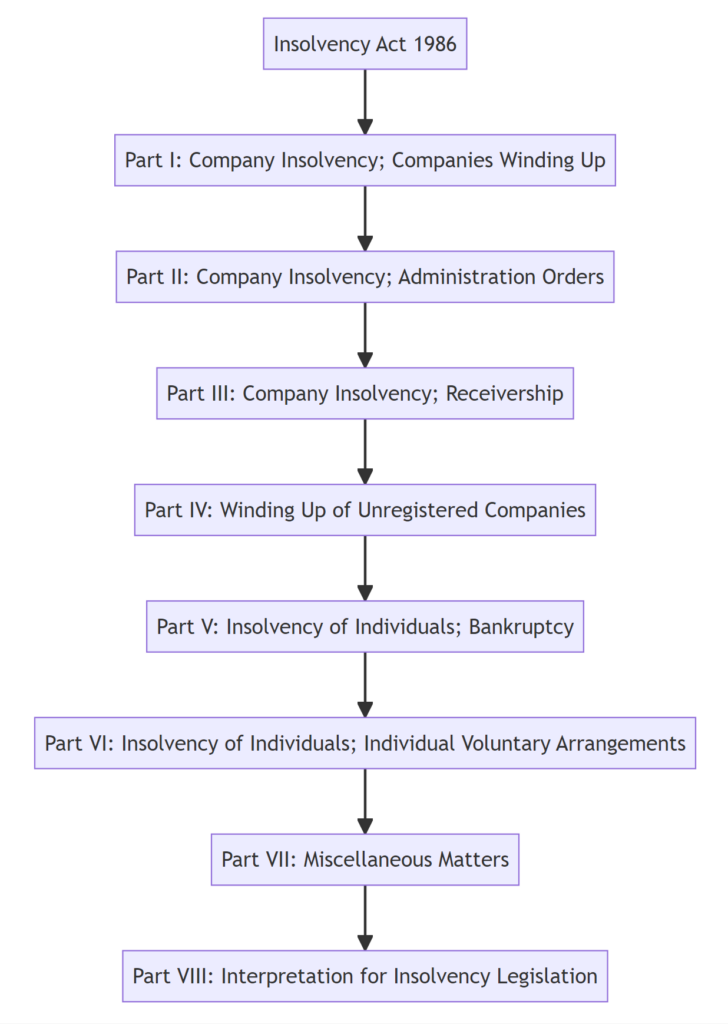

The Insolvency Act 1986 is a pivotal piece of legislation in the United Kingdom that provides a comprehensive framework for dealing with financial distress and insolvency. This Act, which applies to both individuals and companies, outlines the procedures for declaring insolvency, the rights of creditors, and the responsibilities of insolvency practitioners.

The insolvency law, known as the Act, addresses various aspects of business insolvency, including company winding up, administration orders, receivership, and individual bankruptcy. It also covers unregistered companies and voluntary arrangements, as well as creditor claims.

In the following sections, we will provide an overview of the main parts of the Insolvency Act 1986.

Quick Links

- Part I: Company Insolvency; Companies Winding Up

- Part II: Company Insolvency; Administration Orders

- Part III: Company Insolvency; Receivership

- Part IV: Winding Up of Unregistered Companies

- Part V: Insolvency of Individuals; Bankruptcy

- Part VI: Insolvency of Individuals; Individual Voluntary Arrangements

- Part VII: Miscellaneous Matters

- Part VIII: Interpretation for Insolvency Legislation

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What does the Insolvency Act 1986 do?

- What is the English Insolvency Act 1986?

- What is Section 86 of the Insolvency Act?

- Is the Insolvency Act 1986 still in force?

- What is the order of priority in insolvency law 1986?

- What are the purposes of insolvency?

- Who does the Insolvency Act 1986 apply to?

- How long does an insolvency last?

- References

Part I: Company Insolvency; Companies Winding Up

Company insolvency is a state where a business is unable to pay its debts to creditors as they fall due or where the company’s liabilities exceed its assets. The Insolvency Act 1986 provides a detailed framework for dealing with company insolvency, including the process of winding up the trading company.

Winding up, also known as liquidation, is the process of closing down a company and distributing its assets. There are two main types of winding up procedures under the Insolvency Act 1986: compulsory liquidation and voluntary liquidation.

Compulsory liquidation is initiated by a court order, usually following a petition from a creditor, the company itself, or a shareholder. The court will appoint a liquidator to wind up the company if it is satisfied that the company is unable to pay its debts.

Voluntary liquidation is initiated by the company’s directors or members. It can be a members’ voluntary liquidation, where the directors declare that the company can pay its debts and the members decide to wind up the company, or a creditors’ voluntary liquidation, where the company is insolvent and the directors decide to wind up the company.

The role of the liquidator in insolvency law is crucial. The liquidator, as a creditor, is responsible for collecting and selling the company’s assets, paying the company’s debts, and distributing any remaining funds to the company’s shareholders. Additionally, the liquidator has the power to investigate the company’s affairs and the conduct of its directors.

Part II: Company Insolvency; Administration Orders

Administration is another insolvency procedure outlined in the Insolvency Act 1986. It is designed to help companies in financial distress by providing them with protection from their creditors while a plan is developed to save the company, or at least to achieve a better result for the creditors than would be possible if the company were wound up.

An administration order is a court order that places a company under the control of an administrator, who must be a licensed insolvency practitioner. The order imposes a moratorium on legal actions against the company, giving it breathing space to restructure, refinance, or find a buyer.

The role of the administrator in insolvency law is somewhat different from that of a liquidator. While a liquidator’s primary duty is to collect and distribute the company’s assets to its creditors, an administrator’s main goal is to rescue the company as a going concern, or if that is not possible, to achieve a better result for the creditors than would be likely in liquidation.

The administrator has the power to carry on the company’s business and to sell its assets. They also have the power to challenge transactions that were made before the administration order was made, such as transactions at an undervalue or preferences.

Freephone including all mobiles

Part III: Company Insolvency; Receivership

Receivership is another insolvency procedure outlined in the Insolvency Act 1986. It is a process where an independent person (the receiver) is appointed by a creditor to take control of some or all of the company’s assets. This usually happens when a company has defaulted on a loan that is secured by a charge over its assets.

The role of a receiver is different from that of a liquidator or an administrator. A receiver’s primary duty is to collect and sell the charged assets to repay the debt owed to the secured creditor who appointed them. They do not have a duty to all the creditors of the company, unlike a liquidator or an administrator.

The role of a liquidator in receivership is somewhat limited. If a company goes into liquidation while in receivership, the liquidator will take control of any assets that are not subject to the receiver’s control. The liquidator’s role is to collect and distribute these assets to the company’s unsecured creditors, after the secured creditors have been paid.

It’s important to note that the use of administrative receivership has been significantly restricted by the Enterprise Act 2002. Nowadays, administration is the more commonly used procedure when a company is insolvent and a rescue or a better return for creditors is possible.

Part IV: Winding Up of Unregistered Companies

The Insolvency Act 1986 also provides provisions for the winding up of unregistered companies. An unregistered company, for the purposes of the Act, includes any partnership, association or company that is not formed and registered under the Companies Act. This can also include foreign companies that have sufficient connection to England and Wales, such as carrying on business or having assets there.

The process for winding up an unregistered company is similar to that of registered companies. It can be initiated by the company itself, its creditors, or by the Secretary of State. The court can order the winding up of an unregistered company on several grounds, including the company’s inability to pay its debts.

The role of the liquidator in the winding up of unregistered companies is essentially the same as in the winding up of registered companies. The liquidator is responsible for collecting the company’s assets, paying off its debts, and distributing any remaining assets among the members of the company. The liquidator also has the power to investigate the company’s affairs and take legal action where necessary.

Part V: Insolvency of Individuals; Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal status that applies to individuals who are unable to repay their debts. Under the Insolvency Act 1986, bankruptcy is a key method for dealing with the insolvency of individuals. It is a process that involves the assessment, management, and settlement of a person’s debts.

When an individual is declared bankrupt, control of their eligible assets is transferred to a trustee, who is often an insolvency practitioner. The trustee’s role is to sell these assets to repay the individual’s creditors. It’s important to note that while the term ‘liquidator’ is commonly used in the context of company insolvency, the term ‘trustee’ is typically used in the context of individual insolvency or bankruptcy.

The trustee has a range of duties, including but not limited to:

- Collecting and selling the bankrupt’s assets.

- Distributing the proceeds among the creditors.

- Investigating the financial affairs of the bankrupt for the period leading up to bankruptcy.

- Reporting to creditors on the administration of the bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy can have serious implications for the individual involved, including restrictions on obtaining credit and holding certain public offices. However, it also provides an opportunity for the individual to make a fresh start once their debts have been dealt with.

Part VI: Insolvency of Individuals; Individual Voluntary Arrangements

An Individual Voluntary Arrangement (IVA) is a formal and legally-binding agreement between an individual and their creditors to pay back their debts over a period of time. It’s an alternative to bankruptcy and is part of the Insolvency Act 1986. An IVA can be flexible to suit the individual’s circumstances, allowing them to keep assets such as their home or car which might otherwise be sold in bankruptcy.

The role of the insolvency practitioner in an IVA is crucial. In this context, the insolvency practitioner acts as a ‘nominee’ and later a ‘supervisor’, rather than a liquidator. The nominee helps the individual to put together a proposal for the IVA, which details how much they can afford to repay and over what period. The proposal is then sent to the creditors for approval.

If the creditors agree to the IVA, the nominee becomes the supervisor of the arrangement. The supervisor’s role is to monitor the individual’s situation and ensure that they keep up with their repayments. They also distribute the repayments to the creditors.

It’s important to note that an IVA can only be set up by a qualified professional, such as a licensed insolvency practitioner. The insolvency practitioner’s fees are typically taken from the repayments made by the individual.

Part VII: Miscellaneous Matters

The Insolvency Act 1986 also includes a variety of miscellaneous provisions that cover a wide range of topics. These provisions are designed to fill in any gaps and provide additional clarity on certain issues related to insolvency. Some of these provisions include:

- Provisions for dealing with the property of a bankrupt: These provisions outline how the property of a bankrupt individual should be dealt with. This includes any property that is acquired by the individual after the bankruptcy order is made.

- Powers of the court in bankruptcy proceedings: The Act gives the court certain powers in bankruptcy proceedings. This includes the power to decide any question of fact or law arising in the bankruptcy.

- Offences in relation to bankruptcy: The Act outlines various offences that can be committed in relation to bankruptcy. This includes offences such as fraud and the fraudulent disposal of property.

The role of the liquidator in these provisions varies depending on the specific provision. For example, in the case of dealing with the property of a bankrupt, the liquidator would be responsible for collecting and selling the individual’s assets in order to repay their debts. In the case of offences in relation to bankruptcy, the liquidator may be responsible for reporting any suspected offences to the relevant authorities.

Part VIII: Interpretation for Insolvency Legislation

The final part of the Insolvency Act 1986 is dedicated to the interpretation of terms and concepts used throughout the legislation. This section is crucial as it provides clear definitions that help to avoid ambiguity and misinterpretation. Some of the key terms defined in this part include:

- Insolvency: This term refers to the state of being unable to pay debts as they fall due. It can apply to both individuals and companies.

- Liquidation: This is the process of winding up a company, selling its assets, and distributing the proceeds to creditors.

- Bankruptcy: This term refers to a legal status that applies to individuals who are unable to repay their debts.

- Voluntary Arrangement: This is an agreement between a debtor and their creditors to repay debts over a specified period of time.

- Receiver: This is a person appointed to manage the assets and affairs of a company or individual in insolvency proceedings.

The role of the liquidator is pivotal in understanding and applying these terms. As an expert in insolvency, the liquidator must have a thorough understanding of these terms and their implications. They must apply this knowledge in their day-to-day duties, whether it’s managing the liquidation process, dealing with creditors, or advising individuals or companies on insolvency matters.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does the Insolvency Act 1986 do?

The Insolvency Act 1986 is a key piece of legislation that provides the legal framework for dealing with financial distress and insolvency in England and Wales. It sets out the procedures for dealing with insolvent individuals and companies, including bankruptcy, liquidation, administration, and voluntary arrangements. It also outlines the role and responsibilities of insolvency practitioners, such as liquidators.

What is the English Insolvency Act 1986?

The English Insolvency Act 1986 is the primary legislation governing insolvency law in England and Wales. It provides the procedures for dealing with the insolvency of both individuals and companies, and outlines the rights of creditors and the duties of insolvency practitioners.

What is Section 86 of the Insolvency Act?

Section 86 of the Insolvency Act 1986 relates to the dissolution of a company following its winding up. It states that once the affairs of a company have been fully wound up, the liquidator must send a final account to the Registrar of Companies. The company is then dissolved three months after the Registrar registers the account.

Is the Insolvency Act 1986 still in force?

Yes, the Insolvency Act 1986 is still in force. However, it has been amended several times since it was first enacted. These amendments have been made to update the law and to incorporate changes in insolvency practice and procedure.

What is the order of priority in insolvency law 1986?

The Insolvency Act 1986 sets out a specific order of priority for the payment of debts in an insolvency situation. This order prioritises secured creditors and preferential creditors (such as employees) over unsecured creditors. Any remaining assets are then distributed among unsecured creditors on a pro-rata basis.

What are the purposes of insolvency?

The main purposes of insolvency procedures are to repay creditors as much as possible and to distribute the debtor’s assets fairly among the creditors. It also aims to provide a fresh start for individuals or companies who are unable to pay their debts, by discharging remaining debts after assets have been distributed.

Who does the Insolvency Act 1986 apply to?

The Insolvency Act 1986 applies to both individuals and companies in England and Wales that are unable to pay their debts. This includes both incorporated and unincorporated businesses, as well as individuals who are personally insolvent.

How long does an insolvency last?

The length of an insolvency process can vary depending on the specific circumstances. For example, a bankruptcy order against an individual usually lasts for one year, while a company in administration could remain in the process for a year or more. The duration of a liquidation process can also vary, depending on the complexity of the company’s affairs.

References

The primary sources for this article are listed below.

Insolvency Act 1986 (legislation.gov.uk)

Details of our standards for producing accurate, unbiased content can be found in our editorial policy here.